The Bank, the Kiwi, and the King of the Maoris.

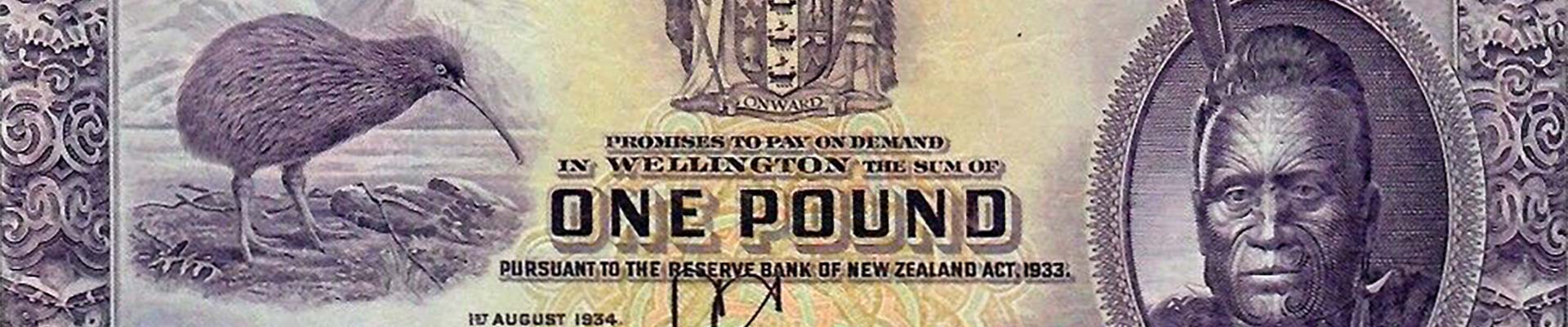

Most of us are familiar with the 1934 Maori series from the Reserve Bank of New Zealand. Ranging from Ten Shillings to Fifty Pounds in denomination, this Depression Era issue is both deservedly popular and scarce. Worth acquiring by any collector in almost all the available grades, it's an iconic issue. The striking design features a lovely Kiwi and King Tawhiao of the Maori on the face, with a scenic view of Milford Sound and Mitre Peak on the reverse. The notes are well known for their beauty, and coveted by collectors of all means. The two photos below show the face and reverse of the lovely Five Pound note, issued in a deep blue, it's perhaps the most striking of the series, both in design, engraving, and chosen color of issue.

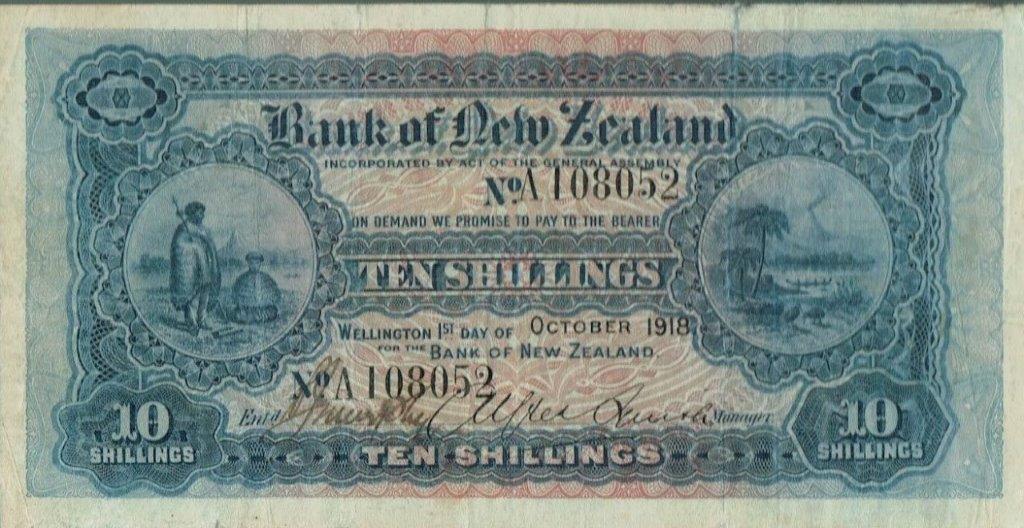

But, long before there was a Reserve Bank of New Zealand, there was the private Bank of New Zealand. The world-wide depression required fiscal 'liberality' by the government, and so the private bank became the federal Reserve Bank of the nation, and issued currency according to the needs of the nation, not the bank's owners and stockholders, who were a bit more conservative in times of fiscal tribulation than Keynesian economics called for. Today, we would call this policy 'monetary easing', the euphemism for turning on the presses at the Treasury to ensure that 'happy days are here again', as the popular song of the Depression called for. So, let's take a look at the Bank of New Zealand and it's issue of 1924, issued in denominations of Ten Shillings to One Hundred Pounds.

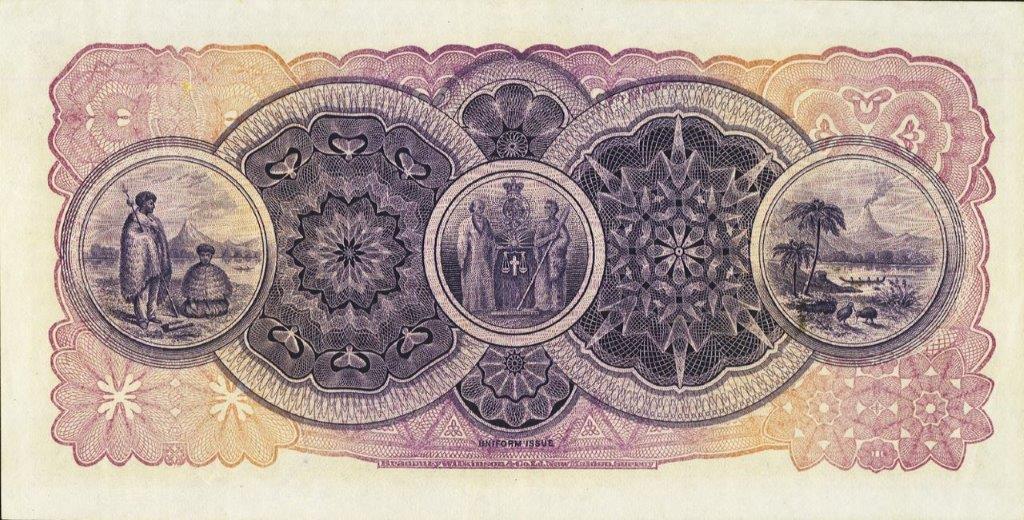

As you can see, both the Reserve Bank and the Bank of New Zealand were clearly frontrunners in the concept and design of banknotes in New Zealand. Both the 1924 and 1934 designs are works of beauty and art. The familiar Kiwi of 1934, is gone from the 1924 series. The wonderful engraved portrait of King Tawhiao, however, is used to good purpose, providing a striking image on all denominations of this not-so-well known series. The reverse of the notes feature the usual filigree and geometry of the period, as well as two little vignettes of New Zealand. The left shows two Maoris in a volcanic landscape, and the right shows two little lost Kiwis foraging for food, a Maori war canoe on the water, and a volcanic background.

Like the American Bank Note Company did throughout Latin America, some designs just deserve to be repeated, don't they? Bradbury, Wilkinson, and Company was the designer and producer of notes for the Bank of New Zealand for nearly 75 years, and used their experience and expertise to good advantage.

Now let's go back just a few more years, to the 1917-1924 Series. Our two Maoris are making their appearance, but still not the first. Our two Kiwis are also scratching around for food, but it's not the first time for them, either. King Tawhiao is absent, and will not appear until the next series in early 1925.

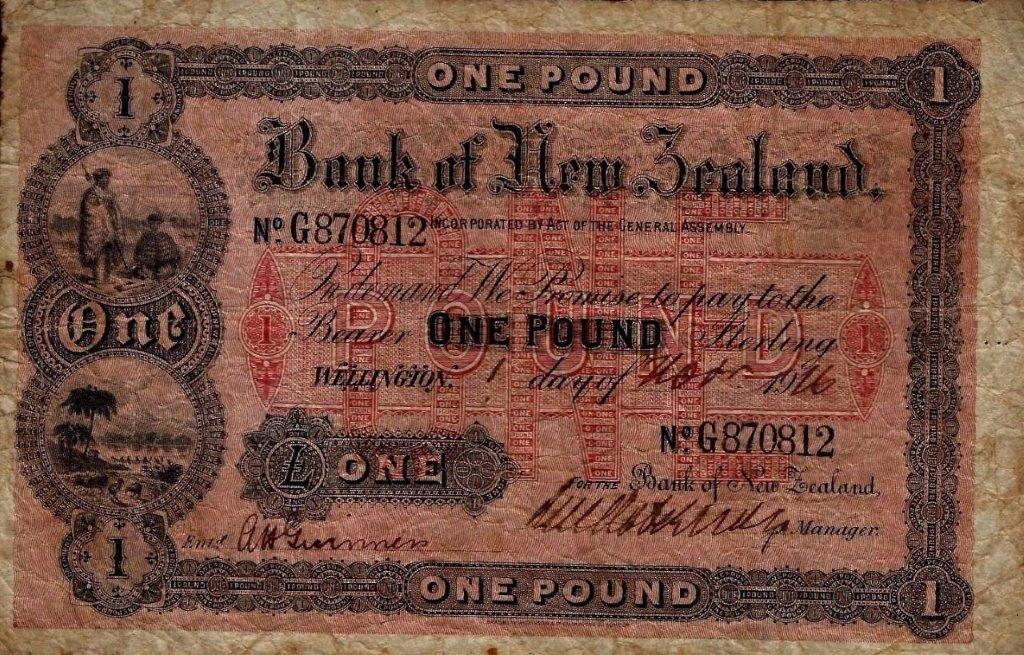

Go back just a few more years, to the early 20th Century, and our hungry Kiwis and Maori idlers are still kicking around. Here are a couple of examples from the Bank of New Zealand and their Sixth Series of 1903. The Fifty Pound note is a lovely example, while the One Pound note is indicative of the condition in which these are generally found.

But, our Maoris and the Kiwis are long-lived, their hunger notwithstanding, for here they again, in their first appearance, on the face of the Third Issue of the Bank of New Zealand. This issue was the longest-running series, from 1870 to 1890.

And so, the Bank, the Kiwi, and the Maori came to be, in mid-Victorian days. These were the first designs of the Colony to depict not only local scenes and wildlife, but to acknowledge the Maori heritage of the islands. They were also the first evidence of the new Identity of the New Zealander, the English colonist, who, only 30 years after the Treaty of Waitangi, were beginning to see themselves not as Englishmen, but as New Zealanders. Kiwis to a man, if you will, and not unlike the American colonists of the 18th Century, destined to make their own way in the world.